There was a point in the summer when I thought that I might make it, even though I had some enormous books on the list. I started off well, then got bogged down in books I’d promised to read and review for NetGalley. I still haven’t managed to succeed in saving them so they don’t expire, so if the deadline is looming, I have to at least try to finish reading. But the real problem this summer was my time being taken up with Other Things, some pleasant, others decidedly less so. I had already decided summer would just have to be extended into September, and the weather fortunately agreed with me.

However, my attempt was doomed – doomed, I tell you! – due to the simple fact that my husband insisted on spending four weeks visiting family in England and swanning around in Devon and Cornwall. That involved lots of walking on sections of the South West Coast Path (immortalised by Raynor Wynn in The Salt Path), visiting gardens and charity shops, where I was forbidden from buying any books. That didn’t stop me looking, but for whatever reason, I hardly spotted anything I wanted this year. That may have to do with the huge number of books I bought in Cornwall last year. Towards the end of the holiday, my other half relented slightly, so I did end up with five new books, about which I hope to write in a separate post.

This will be the third year I’ve taken part in this reading and blogging challenge, hosted most ably by Cathy at 746Books, running from 1 June to 1 September 2023 (or, in my case, the end of September). Actually posting this summery summary has also taken me to the end of October. Doesn’t time fly?

The best laid plans

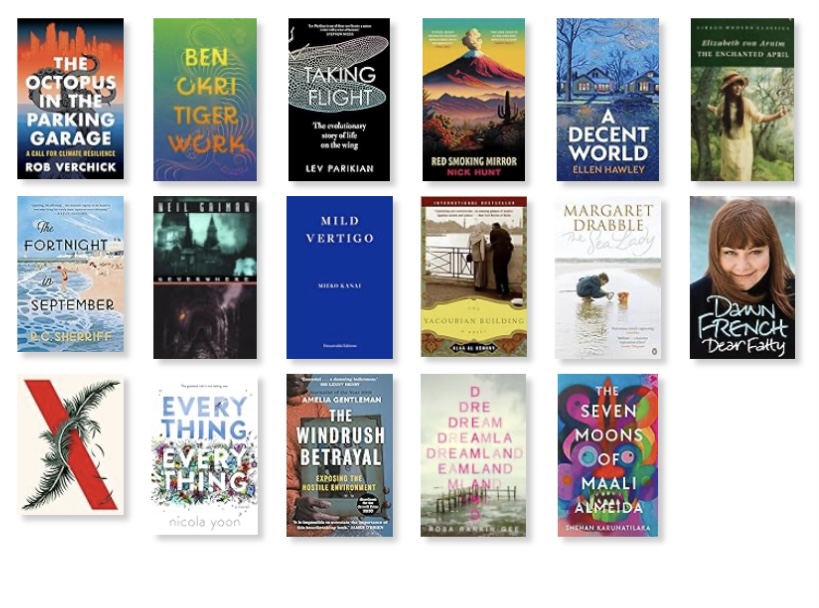

My original list was subdivided into three monthly themes (senses/feelings, calendar and water), which came from a reading challenge on BookCrossing.com. Plus some travel books, as it’s summer, a book I’ve borrowed and want to return, then the ARCs. The photo below was of the physical books I planned to read. I’ll comment on each book, listed in the same order I used back in June. The ones I actually read are in red.

Senses/feelings

- The Man Who Spoke Snakish (2007), Andrush Kivirähk, trans. Christopher Mosely. Status: still TBR.

- Dreamland (2021), Rosa Rankin-Gee. Status: read. I really enjoyed this dystopian novel set in my hometown of Margate after the rising sea levels have changed society and the landscape for ever. Apart from the obvious references to places I know, I enjoyed how the author set her novel in a future that is not too far removed from the worst version of the present. This included social injustices and decisions that have blighted the area for years, such as London using Thanet as a dumping ground for disadvantaged families, but also happier memories and the attempts to make the area more appealing. Fate: passed on to my sister.

- Heimwee naar de jungle (The Lost Steps) (1953), Alejo Carpentier, trans. J.G. Rijkmans. Status: still only half-read.

- Invisible Women (2019), Caroline Criado Perez NF. Status: unread. Fate: to be saved until Nonfiction November.

- Dear Fatty (2008), Dawn French NF. Status: read and enjoyed. Dawn French is generous with her praise of friends and family, reticent on the end of her relationship with Lenny Henry, but her description of meeting and falling in love was wonderful. I made few notes and have retained little, though rereading it, I’ve just discovered a book serendipity that I had forgotten and will add in a forthcoming review. Fate: passed on to my sister, who thinks she may already have read it.

Calendar

- Neverwhere (1997), Neil Gaiman. Status: read. Apart from Coraline (underwhelmed) and his joint novel with Terry Pratchett, Good Omens (brilliant!), this was my first adult Gaiman book, on my shelf since the year it was published. It was well worth the wait. Fate: this will be staying in my personal collection. After all, I think it was my husband who actually ordered it. Likelihood of him reading it? Zero. Chances of my son doing so are considerably higher.

- Spring (2019, Ali Smith. Status: unread. A hardback I did not want to take on holiday. Fate: TBR.

- Summer (2020), Ali Smith. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida (2022), Shehan Karunatilaka. Status: read. Immorality, immortality and betrayal. Gripping, unsettling and multilayered. Certainly not for the squeamish. Hopefully a full review will appear soon. Definitely a worthy winner of the Booker Prize. I also had great fun listening to the author on the Backlisted podcast episode about the Kurt Vonnegut book Galapagos. Fate: returned to the library.

- The Thursday Murder Club (2020), Richard Osman. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (2010), David Mitchell. Status: unread, again. Fate: To read in December, for the BookCrossing theme ‘first names’.

- Time Shelter (2020), Georgi Gospodinov. Status: unread. Fate: TBR, soon.

- The Enchanted April (1922), Elizabeth von Arnim. Status: read. I have started this several times and then set it aside for a time when I could read it at leisure. I managed this at the beginning of August and was duly rewarded with a delightful reading experience. Less happened than I expected, but that was part of the charm. Fate: passed on to my sister.

- Buiten is het maandag (2003), Bernlef. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- A View of the Empire at Sunset (2018), Caryl Phillips. Status: unread. Fate: TBR in October?

Water

- The Hungry Tide (2004), Amitav Ghosh. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- The Sea Lady (2006), Margaret Drabble. Status: read. At the end, I did wonder who the titular sea lady was, but this was a wonderful evocation of a seaside childhood, mostly told in the reminiscences of an ageing marine biologist on a train journey to the north-east, where unbeknownst to him, he will be reunited with a woman he first met as a child. Once lovers, they have kept track of each other’s careers ever since. More Margaret Drabble is on the cards! Highly recommended. Fate: passed on to my sister.

- Watermelon (1995), Marian Keyes. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- Fingersmith (2002), Sarah Waters 1001. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

- Waiting for the Waters to Rise (2010), Maryse Condé. Status: unread. Fate: TBR.

Travel

- The Places in Between (2004), Rory Stewart NF. Status: unread. Fate: TBR in November?

- The Windrush Betrayal: Exposing the Hostile Environment (2019) , Amelia Gentleman. NF. Status: partially read. I started to read this in June, decided to read it on holiday, then had ARCs to read instead. Fate: Finish in Non Fiction November.

- Africa is Not a Country (2022), Dipo Faloyin. Status: unread. Fate: TBR in November.

Borrowed

- Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy (2014), Jeff Vandermeer. Status: read parts 2 and 3 of the trilogy, Authority and Acceptance. Having thoroughly enjoyed and been mystified by the first part last summer, I was really looking forward to reading this and took it on holiday with me. Authority was a real change of pace and left me wishing I understood more. Acceptance had more action and solved some of the mysteries. However, by that point, it was so long since I read part one, Annihilation, that I wasn’t sure who was who anymore, so missed some of the references and found myself flicking back. The end wasn’t as creepy as the beginning, yet was devastating. After reading the first two parts, I couldn’t resist the temptation to watch Alex Garland’s film adaptation, Annihilation, having first ascertained it contained no spoilers. Despite changing everything round entirely and taking huge liberties, with me constantly saying “that’s not what happened in the book”, by the end of the trilogy, I discovered many of the details I hadn’t recognised in the film, did turn up eventually. I would definitely not recommend watching the film before finishing the entire trilogy. In conclusion, I would say the second part of the book was over-long with too much hanging around in bars that didn’t advance the plot. But if you enjoy weird climate fiction/science fiction with creepy and violent elements, it’s definitely worth it. As a bonus, there are some beautiful line drawings at the start of each section. Status: Returned to owner.

Digital ARCs via NetGalley

- Taking Flight: the Evolutionary Story of Life on the Wing (2023), Lev Parikian. Status: read. Lev Parikian is an enthusiastic amateur scientist with a love of observing nature and a Douglas Adams style of humour. Packed with the sort of fascinating facts usually reserved for children’s books, he investigates the power of flight in the natural world, from the usual suspects (birds and insects), to the development of flight in pterosaurs, archaeopteryx and bats. I’m not sure I followed the technical details about the way various insects’ and birds’ wings are attached and move, but I did enjoy factoids such as the fact that some geese can fly upside down, a manoeuvre called whiffling. The book has since been nominated for the 2023 Royal Society Trivedi Science Prize.

- The Octopus in the Parking Garage: A Call for Climate Resilience (2023), Rob Verchick. Status: read. Rob Verchick makes the case for climate resilience rather than hammering on about reducing emissions and large-scale efforts for net zero. Resilience is the ability to absorb adversity, recover and carry on. It often involves growth. He believes there should be more focus on mitigating local effects by building flood defences or the like and ensuring everyone, especially the poorest, lives in safe areas, which may mean abandoning flood plains, etc. He reckons people are more likely to agree to measures that make them feel safer. Sadly I didn’t quite finish it before it expired on NetGalley, so didn’t read his final conclusions. The book gives lots of good examples and also cites some of the thinkers who have inspired the practical solutions. I’m not sure if the increasingly forced octopus metaphors throughput the book are necessary, though it’s fun spotting them. The tone also swings between occasional academic impenetrability and and over-familiar internet speak (“Dunno. […] Something something science.”) On the whole, however, this is a very readable and hopeful look at things that might actually work to keep our planet liveable while the politicians and big business are debating and twiddling their thumbs.

- Mild Vertigo (1997), Mieke Kanai, trans. Polly Barton pub. 21/6 (Fitzcarraldo) 192pp. Status: read. Natsumi is a Japanese housewife who feels irritated by the Sisyphean daily tasks facing her, is slightly nauseated by her husband’s mansplaining and his middle-aged spread, yet is annoyed at the expensive exercise gear taking up space in their apartment. She envies her former classmates who have interesting jobs, yet cannot get round to applying for a job or even taking up a hobby. She spends time talking to her neighbours and observing some of the disturbing behaviour going on. There’s a surprising amount of violence, animal cruelty and dysfunctional behaviour, yet the book is also wry and funny. There’s also a section which is supposedly an article a friend gives her about an art exhibition, which was actually written by Mieke Kanai. There’s an awful lot going on in this novel. I’d really like to read it again. Highly recommended, especially to anyone who has ever spent time as a stay at home mum.

- Tiger Work (2023), Ben Okri, pub. 6/7. Status: read. This is a wide-ranging collection of Nigerian Booker Prize winner Ben Okri’s writing on the climate crisis. This ranges from poetry, serious articles, short stories in various styles, including dystopian, sci-fi and fantastical. The titular poem reminds us that the loss of any species is as terrible as the loss of something popular and obvious like a tiger. We need to find our tiger spirit. I enjoyed the stories most, and I think Okri’s best and most vivid work is when he’s writing about Nigeria. I wasn’t a fan of the poetry, but then I read the lines “Outsider foxes and/Sarcastic wolves” and various other wonderful phrases. I’d say there’s something for everyone here. It’s articulate and thought-provoking, with his trademark magical realism and a varied cast of animals, river goddesses, aliens and even everyday people. The message is clear: we’re ruining our world and we need to show our love for it, not only by protecting the environment in our daily lives, but by taking action and demonstrating against governments and businesses that are destroying the world.

Added to the list

In the course of the summer, I came across a few extra books, as one does.

- Everything, Everything (2015), Nicola Yoon. Status: read. I already had this out of the library, but forgot to add it to my 20 Books of Summer planned reading list. “If my life were a book and you read it backward, nothing would change. Today is the same as yesterday. Tomorrow will be the same as today. In the Book of Maddy, all the chapters are the same. Until Olly.” John Green has competition! If you enjoyed The Fault in Our Stars, then I’m sure you’d love this just as much. The style of writing is wonderfully informal, much of it in flirty emails and text messages. And just like the teenagers in John Green’s smash hit, their conversation is smart and funny, often featuring books; Maddy sums up Lord of the Flies as ‘Boys are savages’. Just like the teenagers in Green’s books, there is a sad secret. Fate: returned to the library.

- A Decent World (2023), Ellen Hawley. Status: read. Digital ARC via NetGalley, chosen for the lovely cover. Margaret Meade: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” The narrator’s grandmother Josie lived her life according to this mantra as a Communist and teacher, later establishing a tutoring organisation for schoolchildren. She never sought revolution. Her aim was simply to create the decent world of the title. Now she has died, her granddaughter Summer is left questioning everything. Should she meet up with Jodie’s estranged rich brother? Does she want to return to her complicated unconventional household with its shifting relationships? Will the older members of the family take away the home where she has cared for her grandmother for the past year? Above all, is it still possible to create a decent world? Lots of interesting characters to get your head around, but an intriguing family saga.

- Dark Matter: a Ghost Story (2010), Michelle Paver. Status: read. This is an extremely atmospheric tale of a young man who joins an expedition to the Arctic. He is told that there is a dark presence at their camp. One by one, the men leave, until Jack is the only one left. “Until now, I hadn’t understood the absolute need for light. I hadn’t appreciated that there’s an unbridgeable difference between a stretch of ‘twilight’ every twenty-four hours, and nothing at all. Only an hour or so of twilight is enough to confirm normality. It allows you to say, Yes, here is the land and the sea and the sky. The world still exists. Without that – when all you can see out the window is black – it’s frightening how quickly you begin to doubt. The suspicion flickers at the edge of your mind: maybe there is nothing beyond those windows. Maybe there is only you in this cabin, and beyond it the dark.” I found this novella at the top of the stairs in our accommodation in Cornwall while on holiday. Downstairs alone, it was very creepy reading. Especially when just as I finished the book, there was an almighty crash of thunder outside that scared the living daylights out of me! Fate: returned to shelf.

- The Fortnight in September (1931), R.C. Sherriff. I spotted this in the library just before we went on holiday and couldn’t resist. It’s about a family’s annual trip to the seaside, starting with their preparations at home and the fraught train journey. They do the same thing every year, staying at the same hotel that is becoming ever more run down. It’s humorous yet poignant, with the father clinging to the past, mother dreading it but loath to spoil the others’ pleasure, eldest son worrying about how to tell his father he doesn’t want to follow in his footsteps. Daughter makes a friend who takes her to meet some young men on the promenade and the youngest son is still a carefree child, but notices all is not well. Even the landlady has something momentous to reveal. This is the real banality of everyday family life, well-observed, with the quirks of human nature to liven it up. There is no hint that, in just a few short years, these young men will be called up to fight in the Second World War. Fate: returned to library.

- The Yacoubian Building (2002), Alaa Al Aswany. Set in a Cairo building that contains people from all walks of life and income levels. There are offices, apartments, businessmen, mistresses (handy for cheating husbands), rich and the poor people living in shacks on the roof. This slim novel gives you insight into the male-female dynamic in Egypt, how some women exert power, and how corruption can make or ruin lives. This is definitely a rich novel that requires concentration and rewards reading in reasonably long stretches. The list of characters helps but it’s quite a challenge to keep track of who’s who as the book flits from person to person, location to location, often with no warning. There is also a useful glossary at the back. It sounds complicated and it is, but well worth it. Read for my book club. Fate: e-boek on Kobo.

Did I read 20 books?

Sadly, no. Counting the second and third parts of the Southern Reach trilogy as two separate books, and The Windrush Betrayal as half-read, I make that 17 1/2 books. But that’s a pretty good total and I read some fantastic books, so I’m happy with that. Thank you, Cathy, for hosting. It’s a great way to decide what to read and I sincerely hope it will be back to challenge me next year.