This is the second part of my post for Liz Dexter’s prompt, ‘Pair a nonfiction book with a fiction book’. This post is about the colonial policy of sending indigenous children to residential schools so they could ‘integrate’ into the white colonisers’ society, thus suppressing and destroying indigenous cultures, languages and family structures. I’ve read so many accounts of this, fictional and biographical, that I decided to make it into a separate post.

This was done in the former British colonies of Canada and Australia up until relatively recently and also in the USA. I am no expert, but I think this was sometimes done only to mixed race children with the excuse that they would never fit in fully with indigenous society, so should be educated to be useful citizens who could adapt to western norms, training boys to work in agriculture and the trades and girls to work in domestic service, often on farms. To achieve this, they were forbidden to speak their native languages and indoctrinated in the Christian religion. If you think about the way English has become a world language in the wake of colonialism, you can see that this policy was used throughout the colonial world, but not necessarily by removing children from their homes. For this post, I’m

INDIGENOUS BOARDING SCHOOLS IN CANADA & USA

NF: Wiijiwaganag: More Than Brothers, Peter Razor. An account of a Native American Ojibwe boy and his immigrant European friend in the repressive residential school system.

NF: In Search of April Raintree – Critical Edition, Beatrice Cullerton Mosioniet, Cheryl Suzack (Ed.). Many years ago, this was the first book I ever read about suppression of cultural identity in colonial residential schools. The original story tells of twin Metis girls (with First Nation and white parents), separated, but staying in contact, and their different experiences. In addition, the book contains critical essays. The story was told in a plain, non-literary style, but for me it was only important as a springboard for the critical essays and further discussion.

Fiction: I asked some Canadian friends on Facebook if they had any suggestions and one came up with this amazing article about residential schools in Canada by Book Riot with both fictional and nonfiction representations of the destruction of culture that the residential school system attempted. Another friend told me about a CBC list of 48 books by Indigenous writers to read to understand residential schools.

ABORIGINAL BOARDING SCHOOLS IN AUSTRALIA

For many years there was a similar policy in Australia to remove mixed race children from their Aboriginal families and communities and take them to boarding schools to teach them white culture and prepare them to work in service or as labourers on farms. They are known as the Stolen Generation. There is a longer reading list on Goodreads.

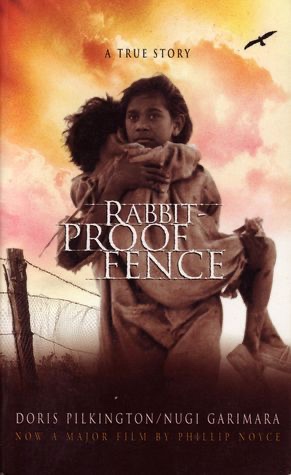

NF: Rabbit-Proof Fence, Doris Pilkington/Nugi Garimara. Aboriginal author. When three young mixed race girls are taken from their homes by the government and shipped away to a boarding school in the south, it doesn’t take long for the eldest to decide they will never thrive under the strict discipline, so unlike their calm and loving home environment. She knows that if they follow the fence that runs from the south of the continent all the way to the north, they will eventually reach their own country. The author was the eldest girl’s daughter and grew up hearing the true story from her mother and aunt. It is interesting, but lacks detail about the school and the trip to make it really come to life. However, it did bring the plight of the Stolen Generations to the foreground when it was filmed.

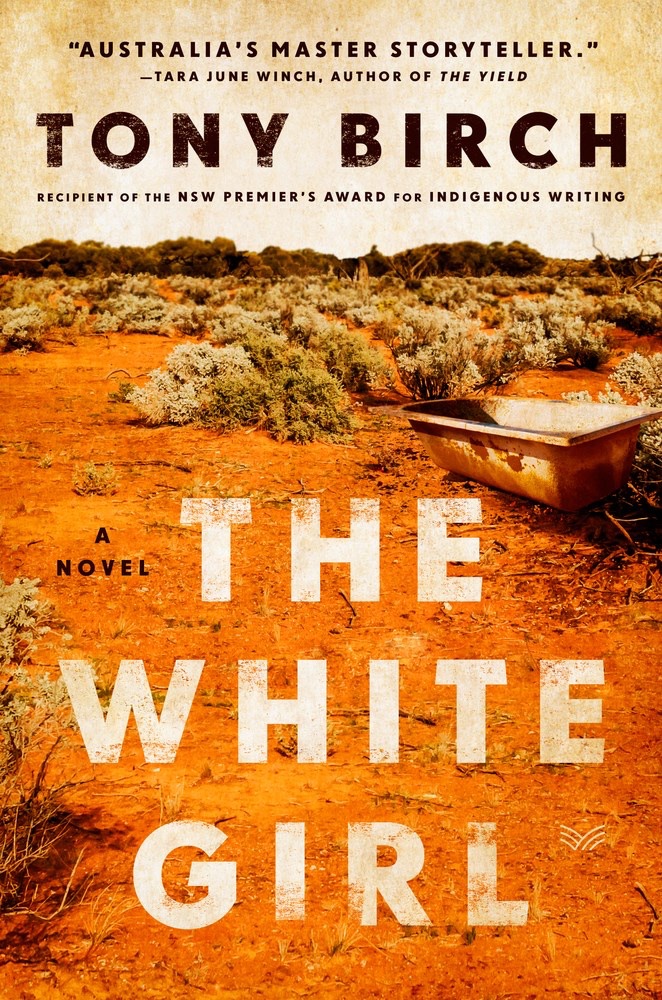

Fiction: The White Girl, Tony Birch. Aboriginal author. An aboriginal grandmother does her utmost to protect her teenaged mixed race granddaughter from being sent to a boarding school. For years this has been possible due to the lackadaisical local policeman. When a new hard-line officer arrives, life becomes much more dangerous. This was beautifully written with great characters. As this has now been published in America, and has even been translated into Dutch and Danish, it is now readily available, unlike many other Australian books.

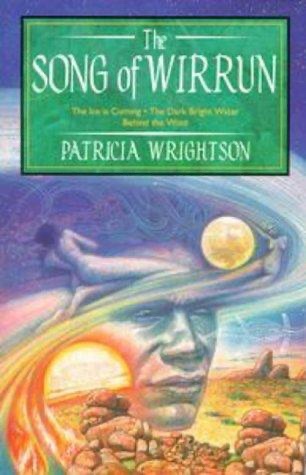

Fiction: The Song of Wirrun, Patricia Wrightson. This one is not about Australian government boarding schools, but I wanted to include it because it strongly reminded me of Rabbit-Proof Fence. It is a fantasy trilogy based on Aboriginal legends and mythical beings. The main character is an Aboriginal teenager who notices that there has been a spate of unusual frosts reported in the newspaper. On a trip into the bush, he wakes covered in frost and from that point on, he is engaged in a struggle against elemental beings that are being displaced by human (white Australian) activity. Various different spirits and beings appear across the trilogy. It would appeal to anyone who enjoys Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea books. However, I believe it is now out of print and I don’t expect it to reappear because it was written by a white Australian who used myths and legends that were not her own. The continent of Australia is so huge that the original inhabitants had a huge range of languages, traditions and stories and she muddled them together as if they all came from one people. That said, I thoroughly enjoyed it, especially the descriptions of landscapes and the physical process of survival in the bush. Wirrun and friends frequently stop in the bush to drink tea and eat dampers (simple flour and water bread) cooked over a fire. I’ve recently been watching a documentary series about Western Australia, presented by comedian Bill Bailey. In more than one episode an Aboriginal guide brewed bush tea and cooks dampers, bringing the book to life. He also explained about how Aboriginal workers used to be paid for their labour in flour, tea (presumably black tea) and sugar, something that is also mentioned in either Rabbit-Proof Fence or The Song of Wirrun.

All these revelations about how my country and other Western people have treated and do treat indigenous peoples make me feel ashamed. At least own voices are now able to make themselves heard. Reading the stories of their ancestors and their own lived experiences is one way to foster understanding for what they have had to endure in the face of colonisation and to open the eyes of those of us who were brought up with visions of a glorious empire. Nary a word spoken about how that was achieved. Educating myself about this is an ongoing process.

Great selections. From my reading, much of the taking of children with mixed heritages, at least in Australia, was designed to then dilute the Indigenous Aboriginal side still further until it had been “bred out”. At least now books can be published and we can learn. I’m trying to pick up on the US side of things now so this post is useful. And thank you for linking back to “my” week!

LikeLike